A new briefing on children, young people and the built environment has shed light on the growing barriers faced by children in accessing outdoor play and getting around independently.

The report emphasises the need for a child-centred approach to planning and urban design, highlighting how the decline in outdoor play over the last century has coincided with rising rates of poor mental health, loneliness and obesity among young people.

It is 50 years since Lady Allen of Hurtwood, the first Fellow of the Institute of Landscape Architects, called on local authorities to ensure that children had more than just playgrounds in which to spend their outdoor time. As the report observes: ‘She wanted local authorities to survey their regions, audit space and provision for play and work across housing, education, parks and public health departments to create playable streets and estates.’

The report observes that children and young people make up more than a fifth of the UK population, yet their freedom to explore local streets and green spaces unsupervised has drastically diminished. Experiences such as playing with friends outdoors or walking to school alone are now increasingly rare.

According to the briefing, many children, especially in deprived areas, have little or no access to safe play spaces. In England, one in eight children lives in a home without a garden; in London, that rises to one in five. Teachers report that some pupils do not go outside at all between leaving school on Friday and returning on Monday morning.

Data from Natural England shows that children from wealthier areas and white ethnic groups spend far more time outdoors than those from deprived backgrounds or Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities.

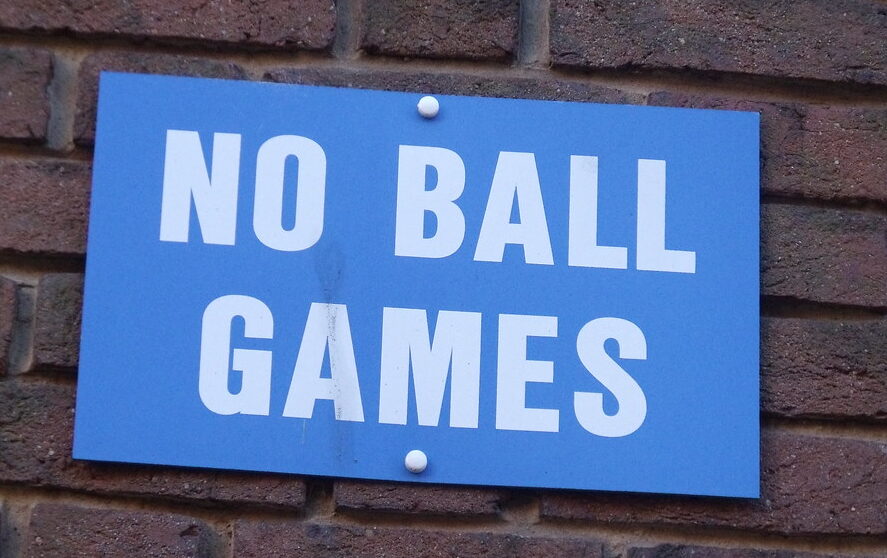

Safety concerns such as traffic, fear of strangers and intolerance of play-related noise, also deter parents from allowing unsupervised outdoor activity. This, the briefing warns, has contributed to what it calls an “anti-play culture,” sometimes reinforced by housing providers banning play altogether.

The report also examines how policy and legislation have shaped children’s interactions with public space, from the Open Spaces Act 1906 to the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014. While responsibility is spread across several government departments, the report notes that the government’s proposed National Development Management Policies: ‘could provide an opportunity for introducing or revising policies which improve outside spaces for children and young people.’

Devolved governments in Scotland and Wales (which in 2012 became the first country in the world to legislate in support of children’s right to

play) already require local authorities to assess whether play opportunities are adequate. Councils in England have no such obligation, although some, such as Leeds and Hackney, have developed local initiatives promoting play-friendly spaces and positive messaging for young people.

In response to the briefing, Play England commented: ‘Play England welcomes this research, which aligns closely with our bold, new 10-year strategy — It All Starts with Play! —and our continued advocacy for a play sufficiency approach embedded within planning policy and local decision-making.

‘Play England’s work is referenced throughout, reflecting our evidence and advocacy on play sufficiency legislation, planning reform, and the need to embed children’s right to play in the design of our towns, cities and neighbourhoods.’

The full briefing can be read here.

Image via Openverse

In related news:

Letting agency launches to bring social purpose to London’s rental market

Leave a Reply